Hildreth Meière Documentary Series - Watch Trailer

Hildreth Meière Documentary Series - Watch Trailer

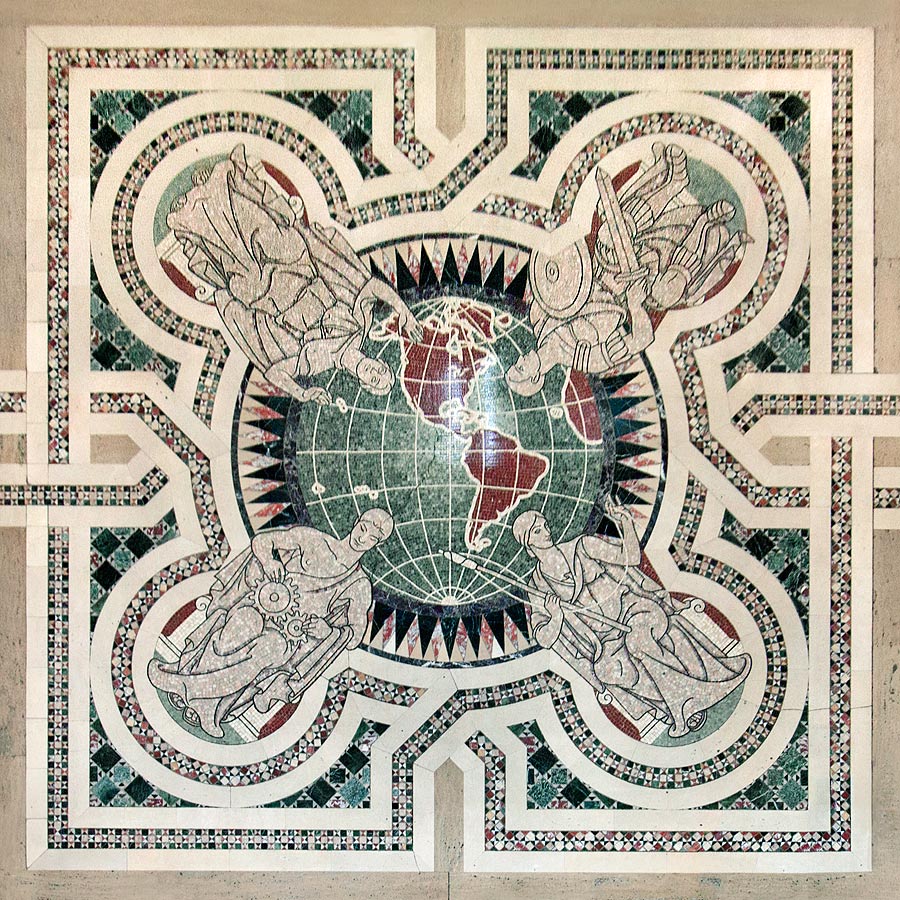

Commissioned by: Taylor & Fisher, Smith & MayMedium: marble mosaic, inlaid marbleExecuted by: De Paoli, del Turco, FoscatoPartially visible

Banking hall floor

Hildreth Meière was commissioned to decorate the banking hall floor of the Baltimore Trust Company Building while she was still creating designs for Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue’s Nebraska State Capitol. A 2002 Historic American Buildings Survey describes the modernity of the Baltimore Trust Building and relates the “sculptural style” of its architecture to that of the Capitol:

The Baltimore Trust Building was cutting-edge design. It was the tallest building in Baltimore when it was built and remained so for several decades. Stylistically, it was the first tall building in the city to eschew the Beaux-arts “attenuated palazzo” formula institutionalized there by Parker & Thomas at the turn of the 20th century, following the Great Fire of 1904. It is contemporary with the Art Deco skyscraper archetype, New York’s Chrysler Building (1928-30), as well as with Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue’s Nebraska State Capitol (1920-32), with which it shares a remarkably similar sculptural style. Furthermore, there is a direct link between the Baltimore project and the decorative programme of the Goodhue building: artist Hildreth Meière [participated] in both. The Baltimore building pre-dates both Radio City Music Hall (1931-6) and the Empire State Building (1930-1).1

Meière divided the long banking hall floor into seven square, inlaid marble panels.2 Four of these panels have central figurative designs executed in marble mosaic. In the middle floor panel, Meière depicted Baltimore Industry as a globe surrounded by four neo-classical, seated male and female figures, each representing a different human virtue: Industry, Cooperation, Vision, and Courage. The theme of virtues recalls Meière’s design on the rotunda dome in Nebraska depicting eight Virtues of the State on which civilized society depends.

Seated figures representing Baltimore Industry on banking hall floor

The seated virtues representing Baltimore Industry in the center floor medallion are described in a brochure published by the bank in 1929:

An unusual motif is employed in the marble mosaic which is most interesting in its symbolism. Conventional borders weave a pattern into which are set several distinct features. The most striking of them is a group of four figures representing those special human virtues—Vision, that quality which enables one to see great things; Courage, the nerve to undertake a task; Industry, the indomitable determination to carry on; and Co-operation, the ability to work with others.3

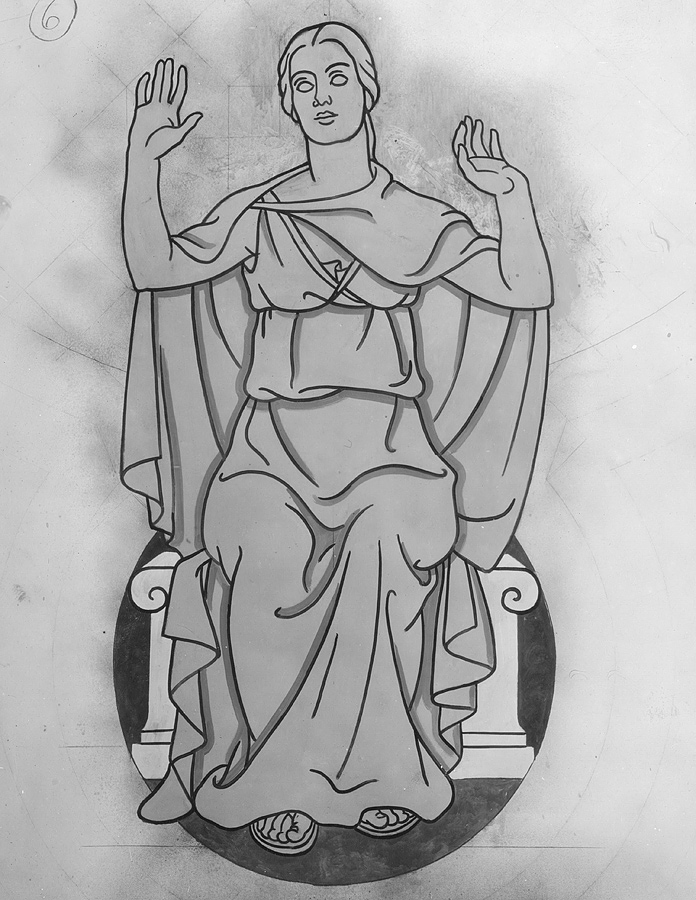

Sketches for Industry and Cooperation

Sketches for Vision and Courage

Meière’s design of seated figures symbolizing human virtues on the Baltimore floor are indebted to her recently completed design of Mother Nature Enthroned on the rotunda floor at the Nebraska State Capitol:

Mother Nature Enthroned, rotunda dome, Nebraska

Sketch for Vision, Baltimore Trust floor

Similarly, Meière’s figure of a female figure spinning to represent the virtue of Industry on the Baltimore floor is an Art Deco adaptation of her figure of a foreseer, who spins the future, on the foyer ceiling in Nebraska:

Ideals of the Future, foyer ceiling, Nebraska

Industry on Baltimore Trust floor

Each of the three additional square panels on the Baltimore floor contains an Art Deco-style female figure executed in marble mosaic representing Baltimore Airport, the Baltimore Rail Center, and Baltimore Harbor. These Art Deco-style figures also recall Meière’s neo-classical figures in Nebraska, but the Baltimore figures have been given a more contemporary twist:

Baltimore Airport

Baltimore Rail Center

Baltimore Harbor

In his review of Meière’s to-scale sketches and full-size cartoons for the Baltimore floor on display at the annual exhibition of the Architectural League of New York in 1930, James Donnell Tilghman describes Meière’s “highly developed sense of the possibility of her mediums as architectural decorations.” He also describes her Baltimore floor as “the most recent example of her courageous pioneering in handling floors as a decorative medium, not merely as a space to be filled with unrelated geometric designs, but as an integral part of the decorative scheme of an architectural erection.”4

Meière’s warmly colored floor decoration depicts Baltimore as a thriving city. The building was completed in December 1929, however, just months after the stock market crash. The Baltimore Trust Company vacated the building in 1933, and for the next sixty years, it had several owners. NationsBank restored the banking hall in 1993 (then merged with Bank of America). The building, now known as 10 Light Street, has been converted to apartments, with the banking hall repurposed as a gym, and the banking hall floor covered over for protection.

Visible, however, is Meière’s design of the floor inside the main entrance at 10 Light Street. In reference to Baltimore’s early history as a seaport, Meière depicted a clipper ship in marble mosaic set into a decorative, square marble panel surrounded by guilloches similar to those on the main floor of the banking hall.

Clipper ship on floor inside 10 Light Street entrance

Built to Last: Ten Enduring Landmarks of Baltimore’s Central Business District, Historic American Buildings Survey, Washington, DC, May 2002. No. 8

For a full discussion, see Catherine Coleman Brawer and Kathleen Murphy Skolnik, The Art Deco Murals of Hildreth Meière (New York: Andrea Monfried Editions, 2014) 133-37.

“The Baltimore Trust,” 1929, n. p.

James Donnell Tilghman, “Baltimore Represented at Architectural Show,” unidentified newspaper clipping, March 2, 1930.