Hildreth Meière Documentary Series - Watch Trailer

Hildreth Meière Documentary Series - Watch Trailer

Hildreth Meière first encountered Raphael Guastavino, Jr. when architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue commissioned her to design decoration for the Great Hall of the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC. The dome of the Great Hall was constructed using the R. Guastavino Company’s patented tile-vaulting system, originally brought to the United States in the late nineteenth century by Rafael Guastavino, Sr. as a means of spanning large spaces without the need of a wooden arch or centering.1

Although the company produced acoustic tile into which Goodhue had wanted Meière to be able to set brightly colored designs in glazed ceramic tile, cost considerations had led the National Academy to cover the underside of the dome in Guastavino’s acoustic plaster rather than to construct it using than his acoustic tile. As a result, Goodhue asked Meière to design decoration in raised painted and gilded gesso that from a distance would give the appearance of glazed ceramic tile set into the structural tile of the dome.

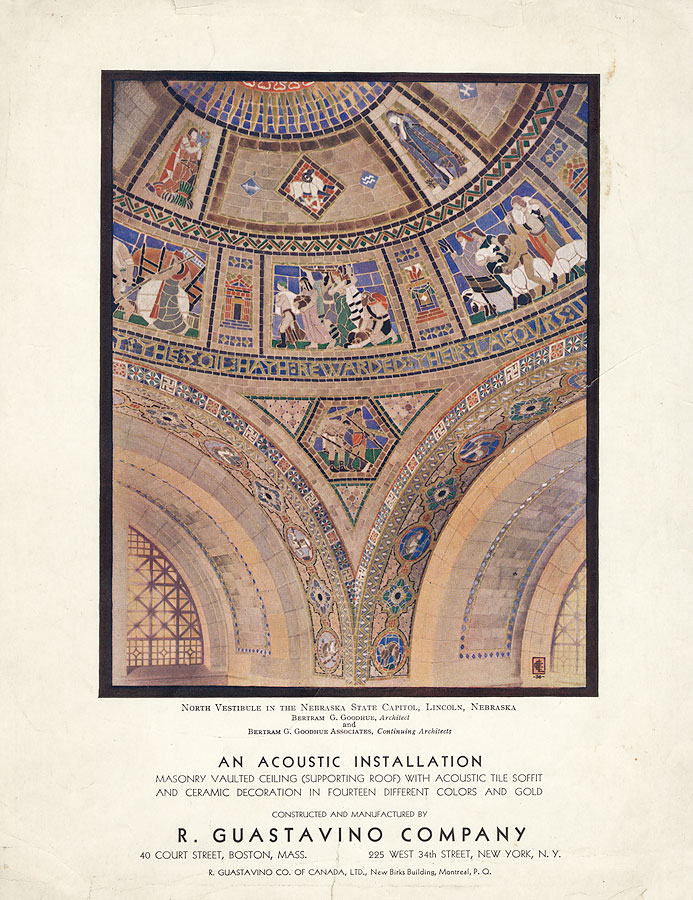

It was not until Goodhue commissioned Meière to decorate the vestibule dome at the Nebraska State Capitol that she collaborated with Rafael Guastavino, Jr. on designing decoration in actual glazed ceramic tile to be set into Guastavino’s patented acoustic tile. The company, which Rafael, Jr. ran from 1908-43, manufactured two types of porous, sound-absorbing tile: Akoustolith, made according to a cold poured, chemically cured process, and Rumford, which was fired in a kiln. Both types, light brown in color, were employed in the domes of the Nebraska State Capitol, into which Meière’s colorful designs in glazed ceramic tile were set.

As had been the case when she decorated the dome of the Great Hall at the National Academy, in order to retain the acoustic properties of the vestibule dome, Meière’s decoration could cover no more than half the dome’s surface. She solved the problem of having to create an all-over design in glazed ceramic tile by limiting its use to narrative vignettes within variously shaped medallions, and surrounding each medallion by Guastavino’s Akoustolith or Rumford tile.

Akoustolith tile surrounds Meière's figurative medallions

Meière provided Guastavino with cartoons that showed the figures in her vignettes segmented into shapes of tile that emphasized their contours. For simplicity, she confined her glazes to Guastavino’s stock colors. Nonetheless, despite her efforts to simplify her designs, the vestibule dome required as many as 5,000 shapes of colored, glazed tile.2 She explained:

The vestibule dome . . . was an experiment, on the part of Mr. Goodhue, Guastavino & Co., and myself. . . . It marks a new use of ceramic tile, and one which is undoubtedly successful. Being new, I had no precedents to refer to and was forced to really originate my style from the necessities of my medium.3

Having established a successful way to incorporate Meière’s designs into the acoustic tile of the vestibule dome, Meière and Guastavino continued to use a similar method to decorate other domes at the capitol.

R. Guastavino Company advertisement, 1930, featuring Meière's to-scale sketch for the vestibule dome of the Nebraska State Capitol, 1924

The R. Guastavino Company advertised the colorful effect they had achieved:

An Acoustic Installation: Masonry vaulted ceiling (supporting roof) with acoustic tile soffit and ceramic decoration in fourteen different colors and gold.

Although the firm credited Bertram G. Goodhue Associates as architects, they failed to credit Meière for her designs.

Meière was recognized for her decoration, however, by the Architectural League of New York, which awarded her their Gold Medal in 1928 for her designs at the Nebraska State Capitol.

She worked again with Guastavino that same year at Rockefeller [Memorial] Chapel at the University of Chicago, where the company incorporated Meière’s designs in colorful glazed ceramic tile into the acoustic tile of the vaults, ribs and apse ceiling. It was the first time that Guastavino and Meière had used glazed ceramic tile to enhance the architecture of a church.

Meière’s final project with the Guastavino Company was in 1939 at the Mary Immaculate Center in Northampton, Pennsylvania, where she decorated the half-dome of the apse. In this instance, Meière actually depicted the seven large figures of the Virgin Mary and Saints in Guastavino’s colored Akoustolith tile, with their facial features painted in black, a technique resembling that used for stained glass.

Catherine Coleman Brawer, Walls Speak: The Narrative Art of Hildreth Meière (St. Bonaventure, New York: St. Bonaventure University, 2009): 23. For a definitive discussion of Guastavino vaulting, see John Ochsendorf, Guastavino Vaulting: The Art of Structural Tile (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010).

See Charles Downing Lay, “Hildreth Meière,” The Arts 14 (July/December 1928): 106.

Hildreth Meière, letter to an unidentified Mrs. Shellenberger, September 9, 1930, Hartley Burr Alexander Papers, Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College, Claremont, California. See also Coleman and Kathleen Murphy Skolnik, The Art Deco Murals of Hildreth Meière (New York; Andrea Monfried Editions, 2014): 60.